Whether you’re a UX writer or you work elsewhere on a team writing internal emails, microcopy for an app, product pages, questions for UX research, or anything in between—the words you write have the power to create a welcoming experience for your readers…or to exclude them.

Inclusive writing is an ongoing, intentional process of actively learning and adapting how we write—in order to create more welcoming and inclusive experiences for our users/readers.

You might assume that it’s a subset of inclusive design, and you’d be right. But what does it look like? In this guide, we’ll look at what inclusive writing is, what it does, and how to do it—using our own hypothetical dating app as an example along the way.

Here’s what we’ll cover:

- What is inclusive writing?

- Why does inclusive writing matter?

- What does inclusive writing accomplish?

- Five steps to writing more inclusive copy

- Frequently missed opportunities to include

- A few other tips to keep in mind

- Wrap up: It doesn’t have to be impossibly massive and complex

Before we dive in I do want to note a couple of things:

In this guide, I’m focusing specifically on inclusion within the context of UX writing, but the steps and guidelines can be applied to many other disciplines and to individual or company communications as a whole.

I also want to recognize that the examples focus more on design/content issues related to gender and sexuality/sexual orientation; this is because I wanted to provide focused examples that follow a theme in order to help you and readers like you to learn in a more focused structured way. And because I am a white, trans, non-binary, UX writer, the real-world examples that live on my devices in the form of screengrabs tend in that direction.

1. What is inclusive writing?

Inclusive writing is the process of writing to intentionally include and create welcoming experiences for more people—particularly those from underrepresented groups.

But inclusive writing is not:

- A one time thing

- Something you can just pay someone else to take care of now and then

- An impossibly massive or “sensitive” topic that’s too complicated to bother with

In the context of UX writing, inclusive copy consists of the written elements within a user experience that actively and intentionally seek to include a broader spectrum of humanity.

So, instead of writing copy with an “average user” in mind, you consider more specific sets of goals and pain points—factoring in the needs of users who many companies, designers, and writers make the mistake of considering “edge cases”—or users “outside the statistical majority.”

Instead of writing to the narrow needs, goals, and demographics included in traditional user personas, you factor in the needs of people who:

- Are Black, Brown, AAPI, Indigenous

- Are non-binary, transgender, intersex, or elsewhere outside the gender binary

- Are neurodivergent, have a disability, or who use an assistive device (like a screen reader)

- Have a mental health condition or considerations

- …and really anyone else with a background, identity, or experience that is underrepresented or marginalized.

Thanks to a couple of proven design principles, when you factor in more specific needs and goals, you actually end up with a user experience that’s better for all of your users! But more on that in the next two sections.

Before we move on it’s important to say that while inclusive writing can require navigating complex ideas and learning about human identities and experiences that are different from our own, inclusive writing does not have to be an impossibly massive and complicated undertaking.

In fact, I would argue that it’s quite simple. Take it from someone who’s experienced that initial learning curve—if you read and really internalize the next three sections, you’ll find that the inclusive approach to writing can become second nature, something you do quite easily.

2. Why does inclusive writing matter?

Simply put: Because people matter. Whether you’re looking to start a career in UX or you’ve got years of experience in the field, that’s an important thing to keep at the center of your work.

Empathy is at the heart of UX design, research, and writing.

Beyond this foundation of empathy, it’s also important to remember this: If we don’t intentionally include, we risk unintentionally excluding.

Kat Holmes writes in her book, Mismatch: How Inclusion Shapes Design, that “the default state for most organizations is a cycle of exclusion.” And exclusion, by nature, prioritizes the needs of a few over the needs of the rest. It takes intentional effort to break that habit and create products and experiences that are inclusive. But this doesn’t mean designing in vague and homogenous ways that somehow “work for everyone.” I love how Kat Holmes articulates this:

“Inclusive design doesn’t mean you’re designing one thing for all people. You’re designing a diversity of ways to participate so that everyone has a sense of belonging.”

And this is 100% true of inclusive writing (as a subset of inclusive design). Write in ways that allow more people to feel that they belong in the user experience.

When people feel excluded, they’re far less likely to return to the experience—or they’ll dread it every step of the way, an outcome that the entire field of UX seeks to prevent!

3. What does inclusive writing accomplish?

Broadly speaking, this inclusive approach to writing accomplishes three things:

- It creates an overall user experience that actually works better for all or most of your current (or target) users.

- It enables you to spot pain points that some of your users would rather not (and shouldn’t have to) experience—and perhaps even resolve those pain points in a way that delights those users with the realization that you’ve addressed and resolved a pain point that’s commonly overlooked or ignored in other digital products and services.

- It has the potential to open up the user experience and make it accessible to whole segments of users that you may not have even realized would want to use your product!

And how does this happen? This is the effect of a design principle known as the Paradox of Specificity, which states that when you design (or in this case, write) to meet a more specific set of user needs, you end up with a product/user experience that actually works better for a lot more people!

The OXO Good Grips vegetable peeler is a classic example of this. Sam Farber wanted to design a kitchen utensil that would work well for his wife, who had arthritis. The result was a product that worked so well for so many people, it ended up in the Museum of Modern Art’s Smart Design Collection!

Going back to the quote from Kat Holmes, when you write inclusively, you’re creating more ways for more people to find that sense of belonging in the micro-moments of your user experience. And this is true for your work whether you’re a UX writer or a copywriter.

4. Five steps to writing more inclusive copy

Step 0: Understand where inclusive copy belongs

In terms of when you should write inclusively, the answer is: Write as inclusively as possible in every moment of the user journey.

But before you go into the writing process to prove to the world just how inclusive you can be, take a moment to consider the larger context:

What are the goals and basic function of the product you’re writing for?

If the product by nature excludes some kinds of people, you should write as inclusively as you can without making an inherent promise to anyone the product is intentionally excluding.

Here’s a dating app example: If you were writing for an app like Parship (very focused on binary gender), you wouldn’t necessarily want to write in a way that makes people of all genders feel welcome when, in fact, they’re not.

What are the values and inclusive actions of the company/client you’re writing for?

It’s not your job to write copy that makes an entire company look more inclusive than it actually is. In fact, doing that can set your users up for disappointment or, at the very least, an incongruent experience. So consider:

- What are your company or client’s values?

- Who do these values benefit or make a promise to?

- Who do they leave out?

- What clear and intentional action does the company/client take to include or benefit a broader spectrum of humanity?

Your writing should be representative of these values and actions. If this is an area where your company needs to do a lot better, write in keeping with where the company is at—but be 5% more inclusive. That’s a vague measure, I know, but here’s what that might look like:

- You’re helping to conduct some user research. This is a great time to influence the process to include a broader spectrum of humanity in the research process. Learn more in our guide on inclusive UX research.

- You’re writing some copy and find a very clear and simple way to be more inclusive that won’t promise a more inclusive experience to people who will be made to feel excluded by the nature of the product itself or by wider company communications. This is a great time to adjust your writing to make it more inclusive!

- You see aspects of the product itself that fail to include. If you’re able, bring these points up to others on the team who can influence product changes! You might need to explain or educate clients and colleagues about why a particular element or feature isn’t inclusive—so do your research, but remember that you don’t have to be an “inclusion expert” to speak up!

- You’re working with older copy within the product (written by someone else and/or a long time ago), and you encounter something that’s pretty horribly outdated or particularly egregious (like commonly used figures of speech that are racist, transphobic, etc.). Learn to recognize and find alternatives for these phrases that can actually do harm to your readers.

Step 1: Check your ego at the door

This is important because you don’t know what you don’t know. But as you do the work of learning inclusion, you’re guaranteed to become aware of just how much you don’t know!

No matter what we write or design, our starting point is our own lived experience—and what we see and how we communicate is influenced by that.

That’s true for everyone, and it’s not inherently a bad thing! But it does mean that we need to do a lot of research and learning to ensure that we’re writing in ways that don’t unintentionally exclude whole groups of people who aren’t entirely similar to ourselves.

And chances are that the more privilege you have, the more learning (and unlearning) you need to do. To understand this better, check out what the University of Edinburgh has to say about intersectionality and privilege.

The work of inclusion requires an open mind, the ability to admit that you don’t know, and the willingness and motivation to learn. There’s not a lot of room in there for personal ego and trying to prove that you know “all the things” when, in fact, you don’t. None of us do. This is a learning process and we’re in it together.

Step 2: Abandon the myth of the “average user”

Say it with me: There is no “average user.”

I’m not denying that statistics are real—and useful! Are there bell curves in your user base? Sure! Should you only write for the users that fall into that portion of the diagram? Absolutely not.

When we write for that narrow portion of our audience, we’re missing out on so many opportunities to connect with so many more people. And the reality is that our users are human beings who live their everyday lives in ways that are every bit as dynamic as our own.

I woke up this morning and made some coffee—which, for me, involves manually grinding beans in a Groenenberg coffee grinder. As it happens, I was able to do that without any additional effort or undue strain, because my brain, eyes, limbs, and digits happen to match up with what the manufacturer had in mind when they designed my coffee maker. But when I wrecked my bike last year and temporarily lost use of my right hand, it was a different story.

Suddenly I found myself navigating the whole experience in a way that the manufacturer clearly hadn’t envisioned. And that was a very temporary impairment to my normal routine. Suffice to say that if the injury had been more permanent, I would have had to ditch a morning routine that I really enjoy—without accommodation from the manufacturer, it just wouldn’t be worth the hassle.

Now, the percentage of Groenenberg’s users who have permanently lost use of a hand or arm is probably quite small (if it exists at all). But what percentage of their users have experienced a temporary hand injury? What percentage might encounter a situational limitation—do they ever need to hold a phone or a child while they prep their morning fuel? That percentage is getting larger.

(Note: This situational-temporary-permanent approach to inclusive design comes from Microsoft Design’s Inclusive Design Toolkit—a fantastic resource for anyone working in or around product development or content management/creation.)

My coffee-making experience is just one small example of how a more inclusive design would benefit more than just one “type” of user. Apply this same example to a digital product—like a dating app. Swiping left or right is a very different experience if your arms, hands, and fingers don’t match up with what the designers/writers had in mind.

Attention to inclusive design in this instance would benefit users whose abilities are permanently, temporarily, or situationally mismatched with the product design. Learn more about this kind of mismatch in Kat Holmes’ book, Mismatch: How Inclusion Shapes Design. I would argue that this kind of consideration has a part to play in truly ethical design.

Step 3: Identify and challenge your assumptions

This is easy to say and more difficult to carry out—because we don’t always know what assumptions we’re making, especially if those assumptions are rooted in things we don’t know.

For example, when I first started writing for the CareerFoundry blog, I assumed (without even realizing it) that everyone who visits will be reading articles the way I read books: with their eyes, and some with glasses to help them see.

But then I was talking to a friend who has low vision and started using a screen reader. I realized that I’d never even considered what it would be like to visit the blog and consume content…using a screen reader. Suddenly useful alt text and directional language became focal points—easy things to attend to that improve the experience for some of our readers.

To get inside your own assumptions regarding your users, think about what users have to do or know or be capable of in order to navigate the user experience the way you have in mind. Then imagine a user who does it differently, draws from an extremely different pool of knowledge and experience, or simply cannot physically interact with the product the way you have in mind. How can you make the user experience work well for them? (Note that this should also factor into user research, but more on that in the next step.)

Step 4: Research, research, research

We’ll keep this one short and then point you to other resources: You cannot write inclusively if you are not gathering insights from the kinds of people you need to write for.

A core concept in inclusive design is to “design with, not for”—and the same is true of writing.

The first step is to do your desk research. Scour the internet. The second is to immerse yourself in the work of designers and writers who actively and intentionally design and write to include—read books, listen to design podcasts, etc.

Devour any reading or other materials from Microsoft Design, Kat Holmes, John Maeda, and Torrey Podmajersky. There are many, many other people and teams doing amazing inclusive design, but this is a starting point!

Next, you need to make sure you’re conducting inclusive user research.

Step 5: Involve more people in the writing and feedback process

Feedback is an essential part of any great writing process—and that is even more true when it comes to inclusive writing.

Get input and feedback from all kinds of people! If the people providing feedback on your writing are a lot like you, reach out to others. The more identities, backgrounds, and experiences you can have represented in your writing process, the better and more inclusive the copy is likely to be.

Again: Design with, not for. Write with, not for. If there’s some copy you really want to make sure works well for more specific members of your audience (say, people with a particular kind of disability), do what you can to get input from someone (or several people) in that community.

If you have colleagues who can provide this input, that’s wonderful! But—this is an important qualifier—do not expect them to provide this input just because “they’re a great colleague.” Compensate them for their time in a way that acknowledges both the cognitive and emotional effort the task requires.

Keep in mind that if you’re asking them to provide input on copy because of (or related to) their unique lived experience, it probably requires more emotional input from them than you might assume. This is especially true for many people from underrepresented communities that more frequently experience exclusion, discrimination, and harassment.

If you find yourself with a case of writers’ block, check out this article: How to overcome creative block.

5. Frequently missed opportunities to include

Now that you have an understanding of what it takes to write inclusive copy, let’s take a look at some often overlooked opportunities for more inclusive copy.

Because copy is an integral part of the research and writing process and appears throughout most user experiences, the specific opportunities to include are endless. UX writers generate copy in the form of research questions and problem statements, surveys and forms, app onboarding, product pages, transactional emails, CTA and button copy, 404 screens, and so much more.

The good news is that no matter where you turn in your design/writing process, you can find ways to make your process and its results more inclusive. The difficulty this presents is in knowing where to start. Now, this list is by no means exhaustive—but it will give you some starting points:

- Account creation/app onboarding

- Default profile settings and placeholder text

- Personalization options

- Connecting personalization to ongoing communications

- Surveys and forms

Let’s look at each of these in a little more detail. As we go along, we’ll include specific examples based on this scenario:

Imagine that we work together on a UX design/writing team, and that we’ve created an app—and just for fun, let’s say it’s a dating app.

Now imagine that someone—we’ll call them Jordan—has discovered our app. “This is awesome,” Jordan says. “Maybe this app is better than all the other ones I’ve tried— maybe I’ll finally find [true love, a good time, a decent hookup, or whatever else they might be looking for]” They’ve looked at the product information, they love our branding, the UI is seamless, and so far they’re impressed—and even cautiously hopeful!

So, Jordan downloads the app. Remember, they’ve already tried a lot of other dating apps—and there’s probably a reason for that. Don’t assume it’s only because Jordan hasn’t found the kind of relationship or connection they’re looking for—since most dating apps bake some addictive/habit forming features into their UX/UI, they’re far more about the journey than the end result.

Right now, we’ve got some rapport with Jordan—even if it’s tenuous. We’ve already accomplished something: through a series of micro-moments, Jordan has become interested enough to try the app.

Going forward, this rapport is ours to keep or lose—regardless of who Jordan is or what’s going on in their life. If we’ve done a relatively good job of all the research, ideation, testing, and iteration (the UX design process), our app will actually provide a great experience for Jordan as they go about finding whatever kind of relationship/connection they’re looking for.

User experiences are full of micro-moments that can powerfully impact how welcome and included (or unwelcome and excluded) people feel as they navigate the user experience. Let’s have a look at some of those moments.

We’ll take our time with the first one—just so we can establish the general perspective you need to take when you write inclusively—and then pick up speed as we go.

Account creation/app onboarding

Jordan has downloaded the app and they open it up to create their profile.

Any way you look at it, this is a new stage in Jordan’s relationship with our product. And this early moment in the user experience is still incredibly easy for Jordan to walk away from! So how do we get it right?

Most dating apps start by asking for some basic information: name, age, gender, what kind of people they’re looking for, and what kind of connections they’re open to; and for a dating app, this makes sense—and Jordan’s expecting it. For the sake of time, we won’t go into every component here, but we’ll focus primarily on one:

How should we ask for Jordan’s gender?

Worst case scenario: Jordan goes to select a gender from the options we provide, and we don’t give them an option that represents (or even attempts to represent) their gender.

If you’re cisgender, this isn’t likely a scenario you’ve encountered—unless it was with a horrifically outdated product. But for people who are transgender, non-binary, or anywhere else beyond the binary, it’s all too common.

Here are the most popular options you’ll find in any kind of app onboarding that requires gender disclosure—most common to least common:

- “Man” or “Woman” (by far the most common)

- “Man,” “Woman,” or “Other” (usually a nod at inclusion, but still implying that some options are “normal” and others are not)

- “Man,” “Woman,” or “Non-binary” (less common, and better—but still not quite there)

If Jordan’s gender is anywhere outside the binary, this is where they’ll probably drop out and delete the app. Because we’re asking them to identify incorrectly or to toss themselves into what I call the “other bucket.”

And because gender is so complex, even the “non-binary” option falls short—Jordan could be agender (without a gender), bi-gender, pangender, genderfluid, or any other gender outside the binary.

And what if Jordan is a woman who wants to indicate in her profile that she is transgender? None of these popular options are enough—especially not for a platform that’s intended to help users navigate the online dating scene (where gender is so often placed at the forefront).

So how do we make this moment more inclusive? For now, I’ll propose three possible solutions for our hypothetical dating app—which we’d need to test with actual users, of course:

- An open text field that allows Jordan to identify their gender however it makes most sense to them.

- A relatively exhaustive, multi-select list that allows Jordan to check as many gender options as are true for them (or that they wish to disclose). Okcupid was the first dating app to offer more gender options, so it wouldn’t be groundbreaking to give people a list including options such as agender, bi-gender, pangender, genderfluid, genderqueer, non-binary, Two-spirit, transgender, and cisgender—in addition to the usual binary options.

- Or—hear me out—we could simply not ask for their gender. I’m not a developer, so I’ve no idea what that would do to the infamous algorithms, but dating app algorithms seem like they might need a little work, anyway. We could ask for pronouns instead and let Jordan share their gender with people whenever and however they’d like. The queer dating app Lex has fully embraced this approach, so our hypothetical app wouldn’t even be the first to do something so different from the norm!

As I said before, this only scratches the surface of how to make app onboarding more inclusive in the online dating industry. We’d also need to consider:

- What information do we ask for and in what order?

- How should we ask for Jordan’s name and age

- How do we let Jordan indicate what kinds of people they want to connect with?

This third point is a big one, and worth an example.

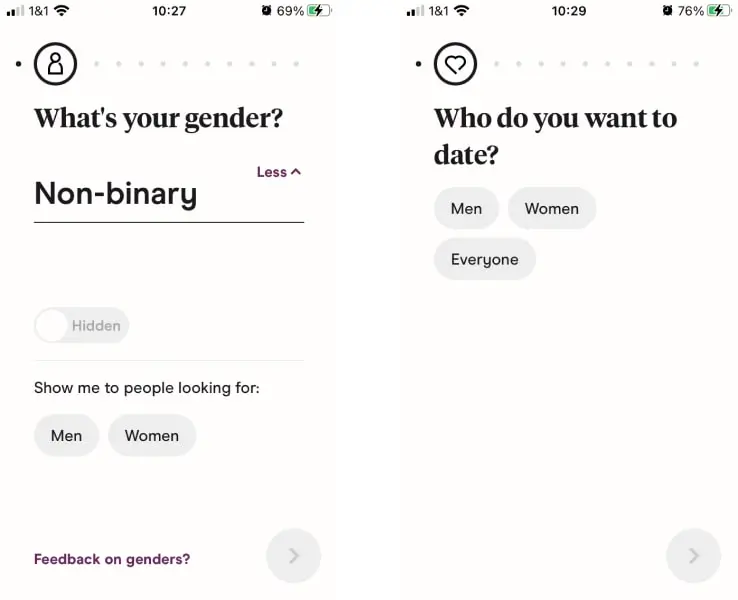

Some dating apps provide a non-binary option for self-identification and then slip back into the binary when they ask the user to indicate interest or who should find their profile—as Hinge does on these two screens (as of this writing, Bumble includes a similar process):

(Screengrab from the author’s phone)

Let’s say Jordan is non-binary and interested in connecting with people of any gender.

With the options on the first screen, Jordan can identify accurately, but then they have to say whether they want to see people who are looking for men or women—even though people looking for men or women might not be looking for someone who is non-binary.

Later in the onboarding process, Jordan is asked who they’re interested in dating and they’re given the options: “men,” “women,” or “everyone.”

The options on the second screen are better (although the “everyone” is a bit broad), but there’s a disconnect between the options on these two screens.

The first question is trying to figure out who the app should show Jordan’s profile to—with options that assume other people’s interest is limited to the binary.

The second question is trying to figure out which profiles to show Jordan—with options beyond the binary. How could the app ensure that not only can Jordan see “everyone’s” profiles, but also be seen by people who are interested in “everyone”?

Granted, I am not a developer and there may be a technical reason somewhere in the coding world for this configuration. But even if there is, it’s still a moment of exclusion and I’d be curious to discover a workaround. It’s an inclusive design problem that needs some ideation, troubleshooting, and testing to solve!

Default profile settings and placeholder text

Imagine that Jordan has created their profile and uploaded some pictures. Now they’re ready to answer some profile questions to give people a sense of who they are and what they’re looking for.

After we’ve already done so much to make sure Jordan can disclose their gender in the best way, let’s not mess it all up by writing questions, placeholder text, or any other in-platform copy that assumes, implies, or makes fun of any race, ability, gender, socioeconomic status, mental health condition, and so on.

These moments are so small, but they make up so much of the overall user experience and can really make or break the experience for the people you forget to take into account!

This kind of copy tends to be deeply rooted in what we know (or don’t know). So most of the work is in learning—conducting inclusive research, getting feedback from a variety of people, and always checking your ego at the door and being willing to learn and course-correct when you realize you wrote something that was actually very racist, ableist, transphobic, etc.

Personalization options

Most of us enjoy being able to personalize app experiences.

For our dating app, we want to make sure that Jordan can personalize the app’s accessibility settings (to provide a better user experience if they have a disability)—but to do that, we’ll need to learn what disabilities we should factor in and create personalization options for. Research, research, research!

We should also make it easy for Jordan to change the name displayed in their profile. People change their names for all kinds of reasons, many of which are deeply personal, and they shouldn’t have to hassle with a profile connected to an old name—particularly if the old name is triggering (as it can be for many transgender people who choose new names).

Beyond this, what if Jordan wants to specify some details that aren’t required in most dating apps—like race, ability, or neurodiversity? Our first step should be…you guessed it. Research!

Will our users who are people of color, people with disabilities, or those who are neurodivergent even want to specify these things? If so, how would they want to specify it? What options should we provide? And do they want to control who sees these details? These are all important questions to ask, and we are guaranteed to learn a lot as we find the answers and design and write accordingly.

Connecting personalization to ongoing communications

Let’s say that we’ve provided Jordan with an amazing, inclusive onboarding process, default settings, profile questions, and personalization options. Great job!

Now imagine that Jordan is transgender and chose to update their name and pronouns in our app.

Note: Let’s not assume all transgender people change their name or pronouns. But Jordan did—and that matters.

Another note: Many dating apps make the name one of those little details you’re not allowed to change later. There are valid reasons for this, I’m sure, but again—I have to wonder if there are other possibilities!

Okay, back to Jordan! They’re enjoying the in-app experience—having conversations, going on dates, and so on. They’re happy! And then they receive an email from us. Based on how we address them, it’s clear that whoever sent the email didn’t see the profile update.

Now, if Jordan made that change very recently, it might hurt, but they’ll probably be pretty understanding. But what if they receive the email (or a second email) a week, a month, or even longer after they made that change?

By way of example, check out this email I received from an airline loyalty program—a few years after I legally changed my name and updated records for all my accounts.

I know there are a lot of ins and outs to this process, and the bigger the company, the more complex it might be. But if you’ve ever been misgendered or called the wrong name, you know that can be awkward (at best). For some people it can be deeply hurtful, triggering, or even harmful. This isn’t something we want Jordan to experience!

We need to do everything in our power to ensure that everyone writing copy across the user experience has access to the most recent user data.

In an ideal scenario, Jordan could update their name and pronouns, then receive an email from us verifying that we’ve got the update. And then every communication after that would use the correct name and pronouns!

Surveys and forms

By now, you know the drill. When we give Jordan a form or survey to fill out, we need to make sure that they understand why we need the information we’re requesting and what we’ll do with it—especially if this includes any personal information (and for a dating app, this is definitely in the mix), or sensitive information such as bank details or social accounts.

Instead of simply tossing the survey or form in Jordan’s direction and hoping they’ll happily just fill it out, we can include copy that explains and reassures them along the way. Here are some examples:

- “We want to [accomplish XYZ]. In order to do that, we’d like to know [information you’re asking for].”

- “We don’t sell or share your information with anyone outside of [company/product name] without your permission.”

- “We just need to know this so that we can [specific thing the info will help you accomplish].”

Beyond explaining things and reassuring Jordan, though, we need to give some attention to:

- What questions we’re asking and why. Do we really need to know their gender or race, or whether they have any disabilities? What will we do with the information? How will our knowing this benefit them?

- What response options we provide. Similar to gender in our dating app onboarding, we need to make sure that we give Jordan options that accurately represent their identity and experience.

If we’re asking Jordan to identify their race, gender, or ability/disability, we need to provide options that represent them. It’s also worth asking how specific or granular the data really needs to be.

For example, do we need to simply know whether or not Jordan has a disability? Should we ask about the specific disability? Or do we need to know what aspects of the user experience are impacted by any disability they have (if they have one)?

The answer depends on why we need to know and what we’re going to do with that information. Curiosity is not reason enough to ask someone to disclose a disability (or any other aspect of their identity and experience). Having a nice graph to show off to investors is probably also not reason enough.

Usually, it’s best to ask for those specifics only when it will have a direct impact on the product—when we have the intention and means to use the information they share to create a better experience for them!

6. A few other tips to keep in mind

Some of these tips have already come up along the way in this guide. But there are plenty more to dive into. Note that this is not exhaustive—I just wanted to provide a few tips to help you get started in your discovery process.

- Follow the inclusive writing process outlined earlier in this guide.

- Ask yourself what you really need to know about your users and why.

- Never assume your readers’ race, gender, or abilities. If it’s necessary and helpful to identify it, simply ask in a way that is inclusive and optional—and clarify why you need to know.

- Never assume that your readers are neurotypical. Neurodiversity is far more common than you might realize, and most digital products could do a better job of designing and writing for their neurodivergent users!

- Write quality alt text for images and avoid directional language.

- If for any reason you’re writing about race, gender, ability, age, mental health, etc., it’s even more important that you do your own research and then talk to people whose identity or experience involves the thing you’re writing about. Get their feedback and learn from them!

And finally, here are some additional resources to get you started:

- Crescendo’s guide to inclusive writing

- How to Design for Every Gender

- Beginner’s Guide to Inclusive Design

- User Persona Spectrums: What they are and how to use them (and learn about voice personas here)

- The Genderbread Person

- Microsoft Design’s Inclusive Design Toolkit

- Mismatch: How Inclusion Shapes Design

- WC3 Web Accessibility Guidelines

7. Wrap up: It doesn’t have to be impossibly massive and complex

Inclusive writing is an incredibly important practice if you’re creating content in any area where other humans (humans who are different from you) will see and interact with it.

As you can probably tell just from reading this guide, it can also seem like a massive and complex undertaking. But it doesn’t have to be—and I don’t write that flippantly!

If we allow inclusion to be an impossibly massive and complex task, it’s unapproachable and we’ll struggle to make it happen. But here’s the key: It’s all about empathy—which, if you’re in UX (or want to be) is at the heart of things anyway.

Follow the five-step process outlined here, dig into the examples and resources, then let your empathy and curiosity take you the rest of the way.

And remember that inclusive design should include imagery and interactions, so it’s absolutely essential that UX and UI designers work together effectively in this!

To learn more about UX writing, check out our reading list: 11 Outstanding Books for UX Writers. And if you want to explore even further, here are a few other guides you’ll find helpful: