UX design is full of laws that, while not strictly laws, can be the making of good design.

Miller’s Law is a key one of these.

If you’re looking to become a UX designer, then this is one of the psychological principles you’re going to have to know.

Far from a dusty old legal theory, this one involves chunks, Netflix, and the magical number seven.

First, we’re going to kick off by defining the term itself, and taking a look at where the concept of Miller’s Law originated.

After that, we’ll analyze the uses of Miller’s Law in UX design, taking a look at some examples of it being deployed.

To skip ahead to a certain section, use this clickable menu:

- What is Miller’s Law?

- How does Miller’s Law work?

- How to use Miller’s Law in UX design

- Five examples of Miller’s Law in UX design

- Final thoughts

1. What is Miller’s Law?

Miller’s Law was conceived in 1956 by the American psychologist George Miller, one of the fathers of cognitive psychology, and, more broadly, cognitive science.

He was concerned with our “working memory”: the brain’s capacity for actively holding multiple bits of information, and our ability to make judgment calls using those items.

Miller’s Law asserts that the immediate memory span of people is limited to approximately seven items, plus or minus two.

So, now that we know what it is, how does it work in reality?

2. How does Miller’s Law work?

Through controlled experiments, Miller found that pushing the number of “bits” of information above this threshold caused confusion, leading to incorrect judgment calls being made. He called this point the “channel capacity”.

The magical number seven

In other words, the number of bits that can be reliably transmitted through a channel (your short term memory), within certain time constraints, is roughly seven. A simple way to remember this is the magical number seven.

So far, so simple. Miller had observed the rule of seven in test conditions, and his theory was holding up. But there was one concern.

Miller found that the memory span of seven was consistent across vastly different types of information. For instance, seven words (each containing multiple letters) exerted the same cognitive load as seven single digit numbers.

His explanation for this phenomenon was a new theory called “chunks”.

What are chunks?

Miller’s conclusion was that the memory span is limited to chunks, not bits, of information. He defined a chunk as the largest meaningful or recognisable unit of information in a larger array of material. So, what counts as a chunk is subjective; their content depends on the knowledge of the person being tested.

For example: a word could be a single chunk for a native speaker. However, to someone totally unfamiliar with the language, this same word would most likely present as a series of phonetic segments—a collection of chunks.

Can I have your number?

This holds true for memorizing long strings of numbers, such as your phone digits. Here’s a quick experiment—have a read and try to memorize this sequence of numbers:

087182349

Close your eyes and try to recall the sequence. Struggling? Now, try again with this format:

(087) 182-349

You should find that this clustering or chunking really aids your brain’s immediate recall.

But what does this all mean for UX design?

3. How to use Miller’s Law in UX design

Your brain initiates a learning process every time you visit a website, or fire up an app on your phone.

Dynamic menus, image carousels, and virtual carts all call on the brain’s ability to learn, navigate, and stay on task to achieve an end goal.

Each needless click, clunky moment of navigation or confusing command adds to the cognitive load. The working memory, where our seven (plus or minus two) items are stored and processed, becomes increasingly crowded.

As the brain receives more information than it can handle, its function begins to slow, decision-making is compromised, and at worst tasks may be abandoned.

Some level of cognitive load is inevitable for the brain when tackling such tasks. The designer’s job is to predict and accommodate the mind’s working limitations in order to serve the user. Working memory overload can be avoided by steering clear of these main pitfalls:

- Too many options

- Lack of clarity

- Too much thought required

Common errors include adding huge menus, long lists of items, too many design elements, and large chunks of written content to your site, all of which cause information overload and may increase your bounce rate.

Instead, remove unnecessary elements and tasks, prioritize readability, minimize choices, and avoid confusing icons. This will relieve the cognitive load on users.

Now let’s take a look at some examples of Miller’s Law in action.

4. Five examples of Miller’s Law in UX design

Netflix

Source: Netflix

The daddy of streaming sites seems to have settled on six as its magic number. Each menu and carousel is presented on the homepage as a separate chunk, offering six options.

From the navigation menu in the site’s header, to the horizontally chunked rows of icons displaying “Trending Now”, or “Popular on Netflix”, the site studiously avoids treading outside of Miller’s recommended limitations.

Even the overtly numbered list of “Top 10 Shows in the U.S. Today” displays with the last four shows obscured.

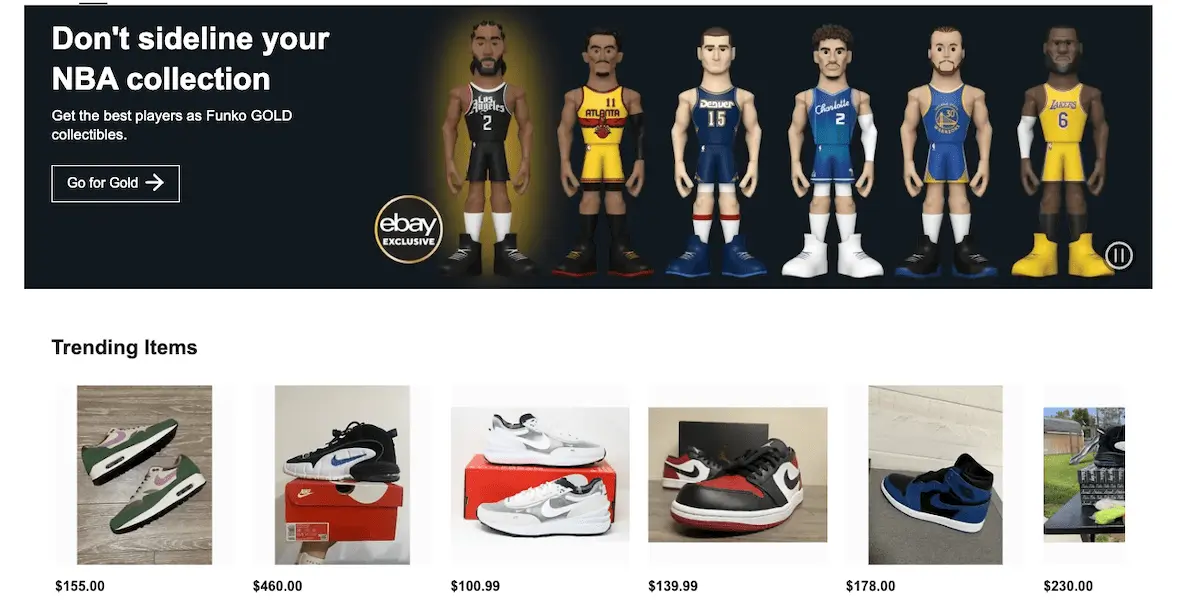

eBay

Source: Ebay

Similarly, care has been taken at eBay to minimize cognitive load and decision paralysis. Despite the huge number of items up for auction, the homepage item gallery stubbornly refuses to expand beyond six images.

Clicking “See all” doesn’t present the user with an endless list. Instead, the auctions are displayed in a scrolling grid, where again around six items are visible at any given time.

Individual auction pages are chunked into sections divided by gray lines:

- A vertical image gallery chunk on the left

- A similar item carousel chunk at the bottom

- A product description chunks in the center

- A seller information chunk on the right

This chunking is crucial for scanning and navigation of the page.

Phone numbers

Number chunks are easier to process, and reduce the cognitive load on those reading them. Strings of digits have been broken up in this way for decades.

In telephone numbers, perhaps the earliest example of Miller’s Law being implemented in UX design, brackets and hyphens create chunks that aid both memorization and vocalization.

Credit card details

With credit card numbers, it’s commonplace to divide the long 16-digit number into four chunks.

The security information on the rear is also often chunked into different sections—using bold, italics, dividing lines, and various fonts to delineate the chunks, and reduce strain on the user.

Blog posts

A key tenet of blog writing is to divide long passages of text into smaller paragraphs (chunks), surrounded by white space, and divided by subheadings.

This increases readability.

Formatting or chunking a blog post (just like this one!) breaks up what would otherwise be a relentless stream of information, making it much easier to digest.

Subheadings also enable readers to easily navigate within the blog, jumping from section to section, depending on what they’re interested in.

Using aesthetically pleasing, content-appropriate typography will reduce distraction for the reader. This will in turn lower their cognitive load, resulting in a better understanding of the content.

5. Final thoughts

Just like Fitt’s Law in UI, one you start to look for it, you’ll realize that Miller’s Law is everywhere in UX design.

From the subtle subdivisions of your chrome drop-down menus, to the carefully grouped delivery options on your last food shop—without these chunks helping us compartmentalize and consume fields of information, we would be quite lost.

Miller’s measurement of our active memory also rings eerily true. But don’t get too hung up on the number seven. Remember, each person’s knowledge and experience will affect their ability to process different sets of information.

Chunks are subjective, but their function is universal: to provide easy ways for users to get to the information they are looking for.

If you’re interested in learning more about the world of UX design, check out these articles: